Pop Culture and the Evolution of Music in Film

Jacy Quint

Jacy Quint

When one goes to see a movie today, it can be predicted that the person is likely to hear a song featured in the movie that they are familiar with. However, popular music was not always a part of the movie-going experience. When film first began to evolve, it was exciting enough to just capture moving pictures on a screen to look at, but as time went on people realized sitting in a silent audience wasn't going over too well (Grusin). As music started to become a more popular part of the movie-going experience, the music heard evolved from live music that was different for every show, to scores created specifically for each film, and finally to soundtracks that are frequently filled with well-known tunes. But exactly how did pop culture music become so integrated in film today?

The first moving pictures ever captured were done so in 1895 by the Lumiere brothers (Lerner). These men made short "movies" of normal, every-day things such as crowds of people or moving trains. Soon after the excitement of being able to simply capture film died off, plots started to develop in movies and silent films started to become popular.

As plots developed, silent films started to become extremely popular. When silent film originated, there was mainly only one genre to see: comedy. Actors used mime, slapstick and many other over-exaggerated visual movements on screen in order to make up for the lack of words used (Evolution). Charlie Chaplin is often considered the best-known comedic silent film actor, most famous for his role in Kid Auto Races at Venice as "Tramp." Chaplin was the face of comedic silent film, so anyone who has seen his work is likely to understand the concept of the comedic genre. Though the name may not look familiar, one who has only seen clips of silent film in their life is likely to still recognize his face. As silent film continued to develop, another genre popped onto the scene: Expressionism. Expressionist silent film used text and more realistic body movement (Evolution); The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari from 1920 is an excellent example of this.

Regardless of the type of silent film being projected, film makers quickly started to realize that audiences would not be happy in a theater sitting in silence for long. The psychological affect that the music played in a film has a huge impact on the way the audience members experienced the film. As film composer Dave Grusin states,

It's not always a conscious thing, but works in the subconscious too ... that's the magic of film-making. We're all dealing with atmosphere, and we try to enhance it for an audience. They don't have to be aware that, 'oh, he just used a square wave and modulated it with eight LFOs.' They shouldn't be aware of it; they should just be made to feel, in some kind of manipulative way ... How you respond to a Mahler symphony will certainly differ from your reaction to a Donna Summer record, but in both cases something happens to you. You're maybe not even aware of it. (Grusin)

As film makers realized that the sound going along with a film is almost just as important as the visuals themselves, they started to incorporate music into the films in order to affect the mood of the viewer. Eventually it came to be that live music was played as the film was projected onto the screen. The number of musicians and instruments in one theater could range from one piano to a full-string quartet; however full orchestras were frequently hired to play in the pit of the theater screen and play live music at each showing of a silent film (Harper). When live music was first introduced to silent film, there was never a score written for the film - the band playing would make up the music as film went along (Cohen). Because of this, the music would be different for every audience. Though the musicians would memorize dramatic parts in the film and eventually be able to play the same general music for each showing, each time the film played the musicians had to improvise (Evolution).

Eventually it became so that film makers were able to synchronize sound to the actors on the screen. The first feature film that has synchronized speech with the actors was The Jazz Singer in 1927 (Evolution). This means that the first words spoken on film were, "Wait a minute! You ain't heard nothin' yet!" These early films with sound were known as "talkies" (Score). Many silent film actors, such as Chaplin, did not survive the switch from silent films to talkies, because the association of their voices and all of the silent film did not go over well with audiences (Harper). This introduced a whole new flood of actors and genres of film.

As silent film started to die out towards the end of the 1920s, musicals started to become extremely popular. Obviously in musicals, the actors stop speaking when a song begins and they continue to sing until the song is over. This is because it was difficult for film makers to come up with a subtle way of mixing speech with music, so the two were still kept separate for a while after talkies were introduced (Evolution). Classical scoring was the way the film makers changed this.

The era of musicals flooding the film scene was short-lived, and film makers began using classical scoring techniques in their films. This technique is still one of the main ways that music is integrated into film today. The classical scoring technique is music in the film that is much like the live bands used in silent film originally, only it was recorded and synchronized to the film so that the music was the same every time the movie was played. So this technique is an orchestra playing in the background of the film, rather than the full song playing that essentially stops the plot like in the musicals (Score). Another difference between this and live music in silent films is that classical scoring technique was used solely to make the audience feel something, rather than to exaggerate the acting on the screen (Harper). It's simple; the orchestra plays music in each scene that reflects the way the audience is supposed to feel. Max Steiner wrote the score of the original King Kong in 1933 using classical scoring techniques (he also wrote the scores for Gone with the Wind and Casablanca), and it was one of the first movies to have a complete score throughout the entire movie (Evolution). More recent films using this same technique including the Harry Potter and Star Wars films, the scores of which were both written by John Williams. However, the classical scoring technique isn't used nearly much today as it used to be, and jazz music was the start of its demise.

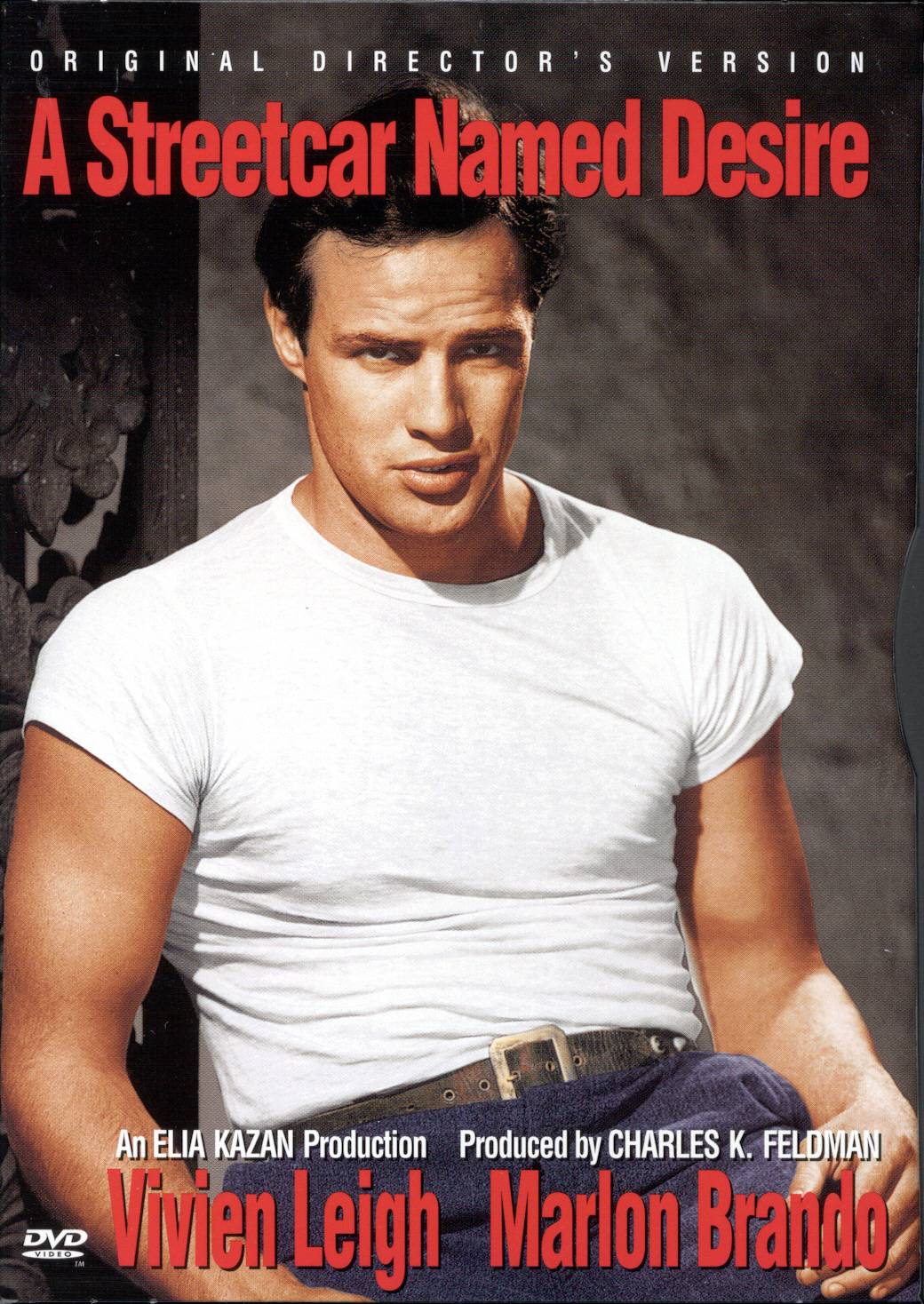

When jazz music became incorporated into film, it was the first time that popular culture had ever entered the movie scene. Jazz music was frequently played at clubs and it was a very "American" genre of music. These beats were usually used to represent fun or sex, making it very different in the film industry than classical scoring. It was introduced to film in the 1930s and was broken down into two different types: "white jazz" and "black jazz." White jazz was frequently used to represent fun or innocence, and black jazz was more used to represent something scandalous or morally questionable (Harper). The film version of A Streetcar Named Desire in 1951 is an excellent example of this and shows how long jazz music was prominent in the film industry.

For a long time, jazz and classical scoring were two main ways of incorporating music into film. However, through the evolution of different genres of music came different genres of scoring. Westerns introduced a new kind of score, as well science fiction and suspense films. Each new genre of film developed a new type of score that assisted the feel of what was happening on the screen (Grusin). The thing that changed the way that music was incorporated into film the most, however, was song scores.

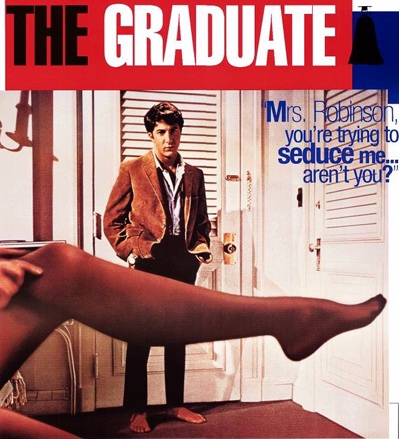

A song score is a score that isn't made for the movie and it isn't made up of classical music or similar themes throughout. Song scores used different songs that are used in the film, mostly made up of songs that haven't been written for the movie (occasionally songs are written specifically for a movie, but aren't continuous throughout the movie). An early successful movie with a song score is The Graduate from 1967, featuring multiple Simon and Garfunkel songs.

However, another advantage to incorporating popular music into film isn't for the benefits of the audience, but for the benefits of Hollywood. Since the song score is typically made up of music that is known to the general audience, they're able to market this. Film makers today will pin a certain song to a movie, popularizing both at the same time (Evolution). When the markets are able to sell soundtracks to a movie made up of the songs used in the song score, it makes it more likely for people to purchase these soundtracks because they are actual songs that they enjoy. Compared to buying a classical score on a CD, viewers are much more likely to be interested in buying a soundtrack with songs that they know and can sing along to (Cohen). Popularizing the movie along with popularizing the songs that are integrated into the movie is like the saying "killing two birds with one stone" for people who make money in the industry; it increases their revenue.

It's difficult to say if a score is better than a soundtrack, because both of them are used to accomplish the same basic goal. They also are both usually successful in affecting the experience of the viewer, but what the soundtrack shows us is that the evolution of music in film was been heavily persuaded by the increase in revenue and by the media in general. The motives behind the evolution in film do not automatically make scores better simply because they are created with the effect of the film, and only the effect of the film, in mind. And while there will always been good examples and bad examples of both soundtracks and scores, one has to keep in mind the importance of the audience. Regardless of the revenue of the music and regardless of whether you can purchase it on a CD or only hear it from a complete orchestra, the most important part of the music in a film is the reaction that it gives the audience. And while it may not necessarily the bad thing that the generation of soundtracks was bred from the desire to create more revenue, it definitely shows us something about the ambitions of people in Hollywood today.